In this column, cult columnist Saoirse takes you on a biweekly jaunt through the obscure annals of the cult film world. We’ll touch on everything from Giallo to J-Horror to Wakaliwood & so much more. If it’s a low budget genre film, or even a big-budget flop with a dogged audience, or even an undiscovered gem, it belongs here.

Today we take a look a creepy and surreal fantasy action film from Hong Kong, The Boxer’s Omen.

Over the years we’ve covered a lot of different kinds of movies from the higher profile realms of The Exorcist III to the more obscure curios of Dark August and The Rainbow Thief. We’ve mined together many corners of weird cinema, but today we explore for the fifth time the world of East Asian Cinema, and by doing so we take a look at one of the most fascinating, strange, and entertaining action pictures and it also functions as a surreal fantasy horror as appropriate for this October season. This fortnight, we investigate The Boxer’s Omen.

Hong Kong has a reputation for producing great action pictures, to the point where multiple films to come out of the country have become definitive to the genre across the whole world. Films like The Way of the Dragon, Police Story, and Hard Boiled across the 70s to the 90s set the template that American filmmakers would forever be trying to recreate and forever failing to. In many ways though, this early template was set by a studio called The Shaw Brothers. Even early on it was in fact them, though, that was setting out to recreate the success of films from across the Pacific. Although the name isn’t a lie, after all it was founded by the Brothers Shaw, the logo that would later become so iconic as to be nabbed by Tarantino for Kill Bill vol. 1, is obviously a cheeky knowing lift from the layout of the Warner Brothers logo. The Shaw Brothers’ films, though, are deeply entwined with the cultural history of Hong Kong, often referring back to their local customs, religions, and martial arts being used to defend the nation against invaders. The language of Cantonese is often a sticking point. If the Western is used by Americans to process their National Identity through stories of its earliest days, so also, to my foreign comprehension, do movies like The 36th Chamber Shaolin.

Starting in the early days doing mainly fairly unremembered historical dramas, with 1966’s masterpiece Come Drink With Me came the beginnings and subtle but sharp transition for the Shaw Brothers into what would make their name, that being dynamic, eccentric, and exciting pulp action films, often also taking on a historical setting. In the 70s films like The Five Fingers of Death, The Five Venoms, and Dirty Ho would break them through in the American cult circuit to the level of notoriety where their films would deeply influence the aesthetic and samples of The Wu Tang Clan and the Tarantino would in fact directly lift a sound effect from The Five Fingers of Death to create the iconic siren from Kill Bill.

The studio would utilize a very similar system to the classical Hollywood system of the 20s through to the 50s, keeping writers, directors, and crew members on contract. While this definitely lead to less than ethical practices happening to members who were under contract, it lead to iconic runs from directors like Chang Cheh, (The Five Venoms, The Crippled Avengers, The Kid With The Golden Arm), and Lau Kar-leung, (Dirty Ho, The 36th Chamber Shaolin, 8 Diagram Pole Fighter), in similar ways to, say, Alexander MacKendrick’s iconic run at Ealing Studios. This way of contracting crew leads to directors feeling constrained and type cast, but it also means they can hone their style and voice with job security, a blessing in the film industry that few can afford. Also taking after the tradition of Roger Corman, intentionally or otherwise, sets were allowed to be reused for different films, enabling huge scale to be achieved on a low budget. All you have to do is spend a lot of money on a big, lavish set once, and you can use it dozens of times, lending scale and grandeur to films for free.

As the 70s wore on and studios like Golden Harvest began to provide stark competition with films like Duel to the Death, with The Shaw Brothers growing in stature, to keep things fresh artistically and commercially, The Shaw Brothers diversified their portfolio. In the process they produced some of the strangest horror and fantasy films the world has ever seen with films like The Oily Maniac, The Bloody Parrot, and today’s entry, The Boxer’s Omen.

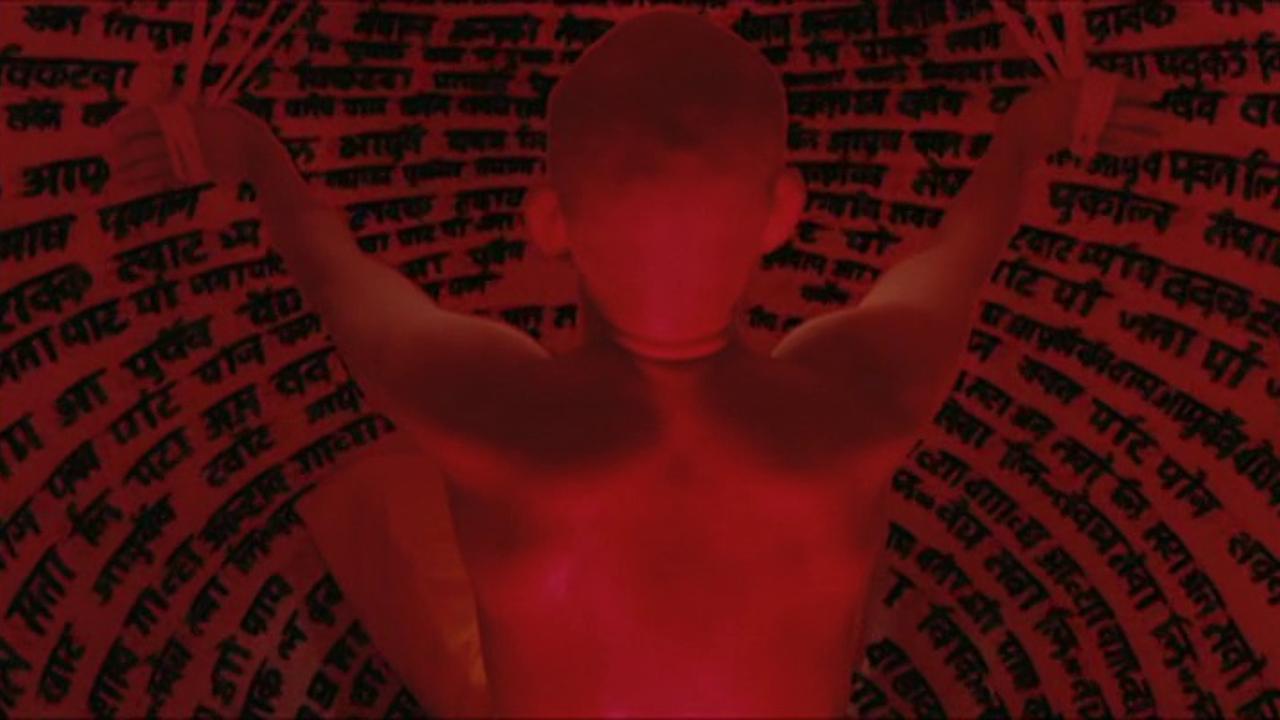

The Boxer’s Omen opens with an exhilarating boxing match between characters only known as “Thai Guy” and “Hong Kong Guy” (don’t worry they will be given names later). It’s a shocking way to be brought into the movie as the punches fly with visceral impact. The style feels at times like a color version of Raging Bull with the camera sitting inside the ring seeing the fists fly or skulking by the ropes like an engrossed spectator. What this does for the overall picture is that when the inciting incident happens and the hulking Thai guy plays dirty, and during a medical break takes the Hong Kong guy off guard launching into a dangerous assault leading to paralysation for his opponent, it is felt intensely, and it makes you feel as motivated as the protagonist. The protagonist in question is Hong Kong guy’s brother, who one day running a meet up with a mainlander criminal to do criminal business with from China, finds himself in another dirty trap as the mainlander surprises him to try to inch into his terf, importantly infracting on traditional modes of conduct in the underbelly. He is saved, though, by a surreal vision of a Buddist monk. This initiates a descent into the world of Buddhist magic that is by turns surreal, entrancing, and transgressively violent.

This film is able to be written about by me today thanks to the new Arrow Video boxset, their second collection of Shaw Brothers pictures including a beautiful new restoration of The Boxer’s Omen. This is a film I have a special relationship with. Although I am not old enough to have rented this movie on VHS at a Blockbuster or had a bootleg passed on to me by a friend in the know or who worked at a store that received import shipping, I had the millennial/Gen Z equivalent. Many years ago, about 6, someone recommended I seek out this movie for a Halloween marathon. Of course I’d never heard of it. The only source I could find to watch it was a full upload to YouTube in 280p. I scoured the internet for a better way to watch it, even for a physical DVD but no, this exported-on-a-potato mess was all that existed in 2017. In much the same way as an 80s bootleg or passed-on VHS, this created a sense of mystique that just doesn’t exist anymore. Like the characters of Ring watching grainy footage of men standing in the oceans and wells and wondering what it could call mean, as if they have stumbled across some dark secret that will leave them accursed, so did I stare at my laptop in my wifi-less property guardianship, as I could barely make out in the pixels such a delights as a woman being turned inside out before pissing blue paint, a man vomiting a cursed eel, and a reanimated bat skeleton in a footrace with a hammer wielding monk. I felt like I had fallen into a strange new world of cinema, and in a way I had. I feel like it was that day I truly fell in love with cult cinema.

Later that year I borrowed an early Arrow DVD of City of the Living Dead from my University Library and I never looked back. I love Arrow because they make cinema like that available, I don’t have to work so hard to discover movies. It was thanks to the explosion of Arrow into the mainstream happening around that period that I was led to discovering films that are now firm favorites for me like Rabid, The Witch Who Came From The Sea, and George Romero’s Season of the Witch. Still, I feel that something is lost. We live in an era where you can get 2k blu rays of films like The Suckling and Night Killer and to a degree, experiences like mine don’t exist anymore. You don’t discover cinema for yourself anymore. You don’t uncover strange stones that you’ve stumbled across anymore. Someone else curates for you and presents all the context for Dr. Butcher, M.D. on a new 4k blu-ray, and while more knowledge, more access is always a good thing, you can no longer be a cinematic flaneur. You can no longer appreciate cinema’s architecture for yourself to the same degree, everything is defined by the structures, presentation, and historiographies constructed by someone else. This is not, wholly, a bad thing, but I do feel something pure is lost. I do feel like The Boxer’s Omen is a different film for being so crisp. In the same way I feel like Eraserhead is a different film for being seen on a Criterion blu-ray and not in some dingy midnight screening.

It would be very easy to sell The Boxer’s Omen purely on those merits. I could fill a thousand words just reeling off the strange delights of this film, but you must discover them for yourself so I shall try to sell it some other way. It does have to be emphasized though, only the hardiest of cinema’s wanderers are prepared for, to be frank, how batshit this movie is. There is not a single second of this movie without something new is being shown, there is not a scene that isn’t digging deeper into the potential of what this kind of movie can deliver. It is a relentless delight. This is not to say this is all the movie has. It would be very easy to imagine the fantastical magical battles this movie contains would exclusively play as a shock-a-second, headache of a movie, and there are moments like that but there are other textures as well. When we first see these visions, especially in a scene where the visions of a monk transforms into television static, the tone is less transgressive but liminal, it draws you in with mystery. To compare it to an American cult film contemporary to The Boxer’s Omen, Videodrome is a transgressive film, but the scene where Max Renn puts his head into his pulsating television is not gory, or horrific, or violent, it’s fascinating and curious and surreal. There is yet an added texture to the scene in The Boxer’s Omen though because it is less to do with the hard steel of modern technology but is more to do with a journey into the warm, intangible boundaries of spirituality. Scenes like this demonstrate that The Boxer’s Omen is a surreal journey into the self in the vein of Jodorowsky. It is in many ways about discovering the Buddhist warrior monk magician that exists in us all. It is a film where the main character shrugs off his alienation with modern society, with a life of girls and violence and money, to battle on the spiritual plane, a place where long sequences of this movie happen. It’s, in a way, like Fight Club if it weren’t so jaded and cynical in that very American way with the spirituality of the natural world.

The film itself has a fascination with the natural world. Most of the film takes place in Thailand, unique for a Shaw Brothers film, and director Kuei Chih-Hung shoots it beautifully. Thailand appears as a world of verdant greens and haunting old buildings steeped in tradition and magic. Crumbled but still standing like the magical tradition that the protagonist has to discover. This, in a way, ties into the whole film’s approach to its magical systems. Now, Shaw Brothers films are not typically known for their literal interpretations of Shaolin training or Buddhist monk living practices, and this film is no different. This is not a film that takes place in any real or recognisable version of Buddhism, however, like all the Shaw Brothers films, it is deeply reverent to the idea of Buddhism. The difference here from most of the known and popular Shaw Brothers films, though, is in those the surreality normally takes place in the byzantine, Kafkaesque methods to mastering the Shaolin ways, that taken at face value make little to no sense but have some small lesson to be learned that pays off in a very satisfying way. Any magical qualities are sort of just implied by the amazing feats the protagonists can accomplish once mastering the Shaolin ways. However, here in The Boxer’s Omen, Buddhist monks are just wizards. The training sequence in this film is actually incredibly short whereas in a film like The 36th Chamber Shaolin it’s the bulk of the movie. They want to rush through that shit to get to the goddamn fucking magical battles! I am very grateful because they kick ass. The film is, as a result, less about physical control than mentale control over temptation, appropriate for a battle against black magic.

The film very well delineates between the magical style of the Buddhists and the villains in this film, very subtly making you root for one more than the other. The less subtle way they do it is that the villain’s magical techniques are just gross. They involve stuff like vomiting onto silk sheets and eating the vomit, decapitating chickens and sprinkling their blood onto skulls, and eviscerating crocodiles. Really though both styles, the good and evil, have a very clear logic to them. They have steps. Maybe you can’t understand the steps but you can tell they’re there. For the Buddhists though, it is much more abstract which conversely makes it more comprehensible. You fail to understand the steps just enough that it seems mystical and curious and aloof, you want to know more. To put it simply, they seem fucking cool. By contrast, the villain’s methods seem more akin to summoning a demon subservient to him and then shouting at the demon what to do until they do it for him, much more the methods of a good, old fashioned hissable villain.

While this film is not a historical investigation into National Identity, it is definitely at play here. By the logic of the structure being a descent, or ascent depending on your point of view, into a historical and forgotten, national, magical tradition, it has to be so. The protagonist is pushed into the narrative by foreigners to Hong Kong, a mainlander Chinese gangster and a Thai boxer, ignoring traditional modes of etiquette in battle and cheating. Similarly, it is his own relationship to modern vices and his alienation from traditional discipline over the self, from the perspective of the movie anyway, that scuppers him towards the end of the second act. It is through this journey into the past that The Boxer’s Omen manages to tie together the disparate themes of Hong Kong being an island with a contentious relationship to nationality, control over the self, and standing as an individual against encroaching forces. There’s meaning behind the quest facilitating the dead priest of the temple being in order for him to attain his true form through the temple standing strong and alone. Then again, this might just be me imposing my Western understanding on this film. There is a disturbing lack of literature on this film out there for me to study so a lot of this I have had to come up with on my own.

Before we sign off, I want a brief note on Mona Fong, the producer of this movie. Already a popular pop star and singer, Mona married into the Shaw fold, and went on to produce hundreds of Shaw Brothers films, often their best. It seems to me that it is in no small part down to her maniacal and singular creative vision that the studio managed to achieve the heights that it did. I doubt anyone else but Mona would sign off on a picture like The Boxer’s Omen and God bless her for it. She was a total badass and a shamefully overlooked figure in film history.

The Shaw Brothers stand tall over cinema and I’m sure we will cover a lot more of their catalog as this column pushes forward into a new era. There’s so much more ground to cover, although probably not a lot quite as strange and singular as this picture.