I’ve written about a number of Korean films on this site over the years. I believe the first one was Bong Joon-ho’s Memories of Murder, which was followed by a number of films from Kim Jee-woon (who has a new film coming fairly soon titled Cobweb which I’m looking forward to), but to my surprise and amazement, I have never reviewed a single film by the great Park Chan-wook. Nor have my peers, which is strange considering we’re all collectively fans of his and his films. Though not an intentional oversight on our part, it’s one I found quite strange. My decision to revisit his 2003 revenge classic Oldboy was not an attempt to correct this negligence however, nor to coincide with the release of his upcoming new HBO miniseries The Sympathizer this April. It wasn’t even done in time for the film’s 20th anniversary last year. I simply decided to rewatch it because it had been a long time since my last viewing of it, and despite having seen it multiple times, I was still starstruck by the craft and emotional weight Oldboy retains.

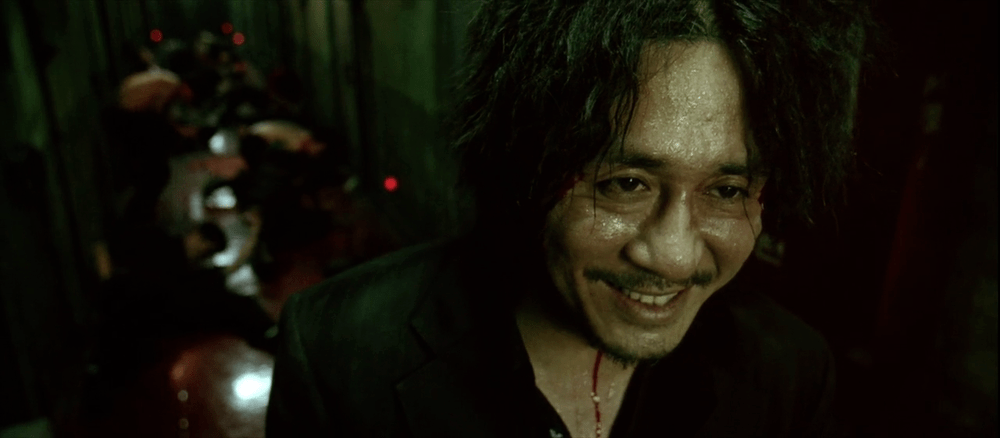

Most of you reading this already know the story of Oldboy but just in case I’ll give you a brief summary, the elevator pitch version of the film. A drunk salesman named Oh Dae-su (Choi Min-sik) is imprisoned in a mysterious prison cell for 15 years, and once he’s let out seeks vengeance on his captors. That’s pretty much all you should know about the film if you’ve never seen it before. This is one of those films you’ll definitely want to see as blindly as possible because of the many surprising twists and turns the story takes throughout.

Rewatching it again, I was amazed at how confidently director Park tells the story visually, using a wide variety of cinematic tools at his disposal to make it even more powerful on a dramatic level. Cinematographer Chung Chung-hoon utilizes crane shots, handheld camera, tilted angles and of course, that long take hallway scene to give the film its baroque visual style and use of purple and green to visually highlight the surreality of Park’s vision. Kim Sang-bum’s employment of non-chronological yet fast-paced editing along with unusual scene transitions keep the film moving along at a brisk pace, and helps make Oldboy something more than just your standard revenge story. Ryu Seong-hie’s baroque production design gives us an idea of the strange and surreal nature of the world and characters the film is depicting. These techniques also allow the viewer to easier grasp the sometimes fantastical story beats that simply would never happen in real life. But it makes sense on an emotional level, and because the film at times has the feeling of a surreal nightmare we are always onboard with any stylization or leaps in logic the film takes without ever feeling like the filmmakers are inconsistent and lazy. And if you want an example of how a grittier and more realistic approach wouldn’t work for this story, just check out the American remake from 2013, which tells virtually the same story beat for beat but removes the surreal style, making the bizarre narrative loose bite and believability strangely enough. By making it less real, we somehow believe the story and characters more. We have left the real world behind, for a nightmarish world of violence, betrayal of trust and bloody vengeance.

What does feel real in the film are the intense and heated emotions that lie at the center of Oldboy. As violent and oftentimes funny the film is, it never forgets that at its core the film is dealing with human characters, principally the protagonist and antagonist, both of whom have based their lives around the deeply rooted desire for revenge. By pursuing this very negative emotion they single handedly destroy not only their own lives but also any possibility of future happiness. Revenge becomes the only thing they live for, and once said revenge is fulfilled, what can they do? It’s a classic tragedy in that sense, and just like any great tragedy the more gut wrenching the ending, the greater the catharsis the viewer will experience upon completing the film. That I think is the key to why the film is so often revisited and remains so beloved. It’s dark without ever becoming too heavy and depressing, it’s a tragedy that reveals deeply rooted emotions at the heart of the human experience, and seeing it on screen can help viewers feel cleansed by that.

I don’t necessarily believe that a film can be perfect, but if you were to make that argument, there are few better films you could choose than Park Chan-wook’s Oldboy. Memories of Murder remains my favorite Korean film and one of my all-time favorite films in general, so me calling Oldboy perfect should be a clear indicator of just how good this film is.